In conversation: Natalya Hrytsak

Natalya Hrytsak is a textile artist and works at the Hutsul Museum (formally the National Museum of Hutsulshchyna and Pokuttya Folk Arts) as the Head of Exhibitions where she manages current exhibitions including occasionally in the role of a curator. She holds degrees in design from the Kosiv Institute of Applied and Decorative Arts and the Lviv National Academy of Arts.

Last we spoke, you were living and working in Zhovka as a museum attendant and artist. What are you up to today?

I currently work at the Hustul Museum in Kolomiya where I take on a whole range of managerial and curatorial responsibilities. It’s both challenging and rewarding; sometimes I feel that we lack the resources we need for the scale and quality we aspire to present but nonetheless, the museum is an incredible well of inspiration for me and for dozens of artists and ethnographers in the region. We are so lucky that we are able to continue to operate and to host visitors during the war while many other museums are closed - their collections damaged, stored off-site for protection from Russian attacks, or flat-out stolen.

Do you feel that the role of the museum has changed since the full-scale invasion?

Our biggest challenge and mission as a museum is to display cultural heritage in a way that conveys its value to visitors. It’s not just about putting on a pretty exhibition, but about constructing the historical context around the object to transmit their cultural and historical value.

If people understand the value of museum pieces, they will also begin to understand the value of their own contemporary culture, which directly informs national culture and nationhood.

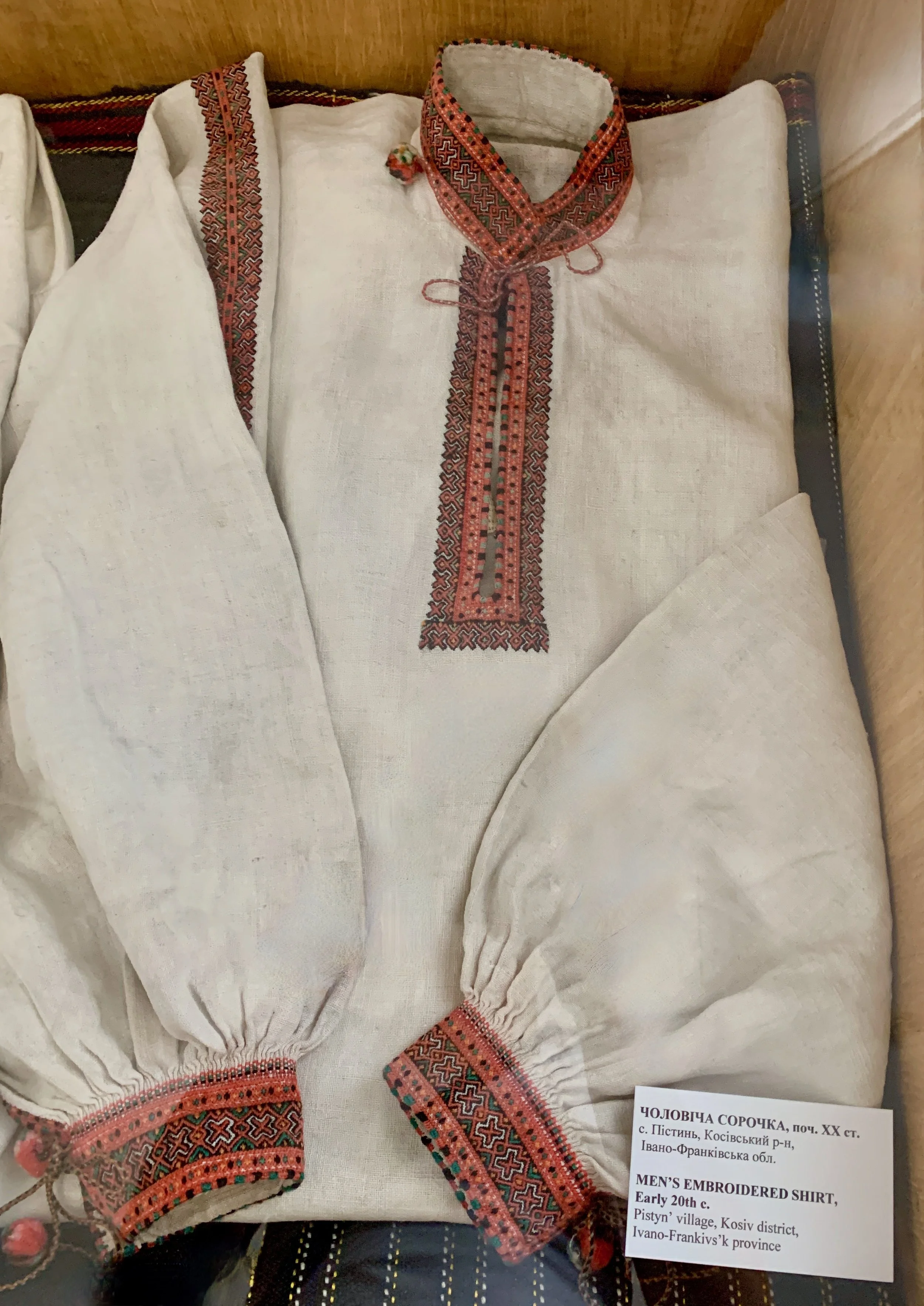

Preservation is another responsibility of the museum. We don’t just want to say, “Look, here’s a 100-year old shirt,” but rather provoke questions around “Why was it sewn this way? What materials were used? What does this reveal about the times and how did that inform the way we live today?”

The shirt we preserve is a unique moment in history. It was likely made by hand and it’s a source of inspiration for our designers today. These shirts were rarely made for sale, but rather were made by individuals for people in their families, for people that they cared about. They were imbued with well-wishes from the maker for the wearer. Beyond its functional purpose, the shirt carries with it a much deeper meaning.

And what I find so fascinating about decorative and applied arts is that these object were part of the daily life of their users. What was created, how it was designed, and the materials used reveal the values and rituals of the time and help place the nation into a larger global context. To take the example of an embroidered shirt - the dyes or threads may have been imported - their reveals trade routes along which intercultural exchange took place. Similarly, the symbols were influenced by those of neighboring cultures and demonstrate our shared histories

Back to the topic of contemporary culture, what has it been like to experience the changes within your city over the course of the last year?

After the full scale invasion many cities really changed. There has also been an increase in interesting people in town like poets and writers who are giving lectures and enriching the culture here.

At the museum we’ve had a lot of visitors from the Kharkiv and Dnipro Oblasts (states). They are curious to learn more and get to know this region. We’ve also hosted soldiers. It’s a two way experience and a really interesting exchange of cultures - they are learning about us, and we are learning so much from them.

This is so interesting. I spent some time working with Ukrainer, an amazing multi-media project, which many years ago began documenting and sharing the diversity of Ukraine with Ukrainians. They described that for some time, Ukrainians knew little about regions of the country that were far away from their own. It sounds like today there is this incredible opportunity to interact with and form relationships with other Ukrainians in a way that would likely not have happened otherwise.

Definitely. Over the last year I have taken to heart the idea that you really cannot judge people based on stereotypes. There is a diversity of “types” of people in eastern and western Ukraine. People are complex and they will surprise you. There are many local Kolomiyan’s who aren’t really interested in culture and have never visited the museum, and there are many from the east who are super interested in culture. These experiences have helped me start to break down stereotypes. You realize that you can only judge based on your own experiences, rather than what you hear others say.

The other thing that I have learned from this war is that planning is a luxury. You only have this moment. Before the full-scale invasion I would set a plan and make goals for the year. Last February, I just had to toss that plan to the side. I realized it’s still OK to make plans, but you make them with the expectation that they will change. I used to think that I was flexible and I had read about these ideas in theory, but it’s really different to experience it.

You cannot live life according to a series of templates; templates about what people are/will be like, or how life should unfold. You can’t hold strict expectations and it’s not a tragedy if plans are turned upside down.

Switching gears a bit, can you talk a bit about your creative process and work?

I love literature and my work is often inspired by what I read. I don’t necessarily pick up a book and think “OK I need to read something to inspire my work. ” Coincidentally what I read often sparks my creativity. For example, the piece titled Dawn/Світанок is inspired by Taras Melnychuk’s poems about dew. I find dew a fascinating concept. For some the morning is the beginning of life and for others (for dew) it’s the end. This piece reflects that moment when dew evaporates.

However, since the full scale invasion I have had to pause most creative work. It’s been harder to be creative. The mind space just isn’t there. In February 2022, all I wanted was to be directly productive and to volunteer.

In those immediate moments following the attack, there is no time or space for reflection on the situation. Creativity was just not part of the conversation. You need some time to pass to be able to look back and reflect on your experiences and to begin to think more deeply about everything that has transpired.

Now that more than a year has passed we understand the important role that this reflection will play in our victory. I am looking for a way to communicate my experiences and thoughts to others. I recently began a new piece - I am not sure how it will finish, but I hope it will incite a series of work.

As an example, I realized that I used to take photos of pretty moments in my daily life… a beautiful window or tree that I might notice as I was walking along the street. But over the last year I have really only taken photos for practical purposes or if someone asks me to take a picture of something. I am only now returning to a place where my mind has space for more and I can really notice the beauty around me.