In conversation: Olena Konohorova

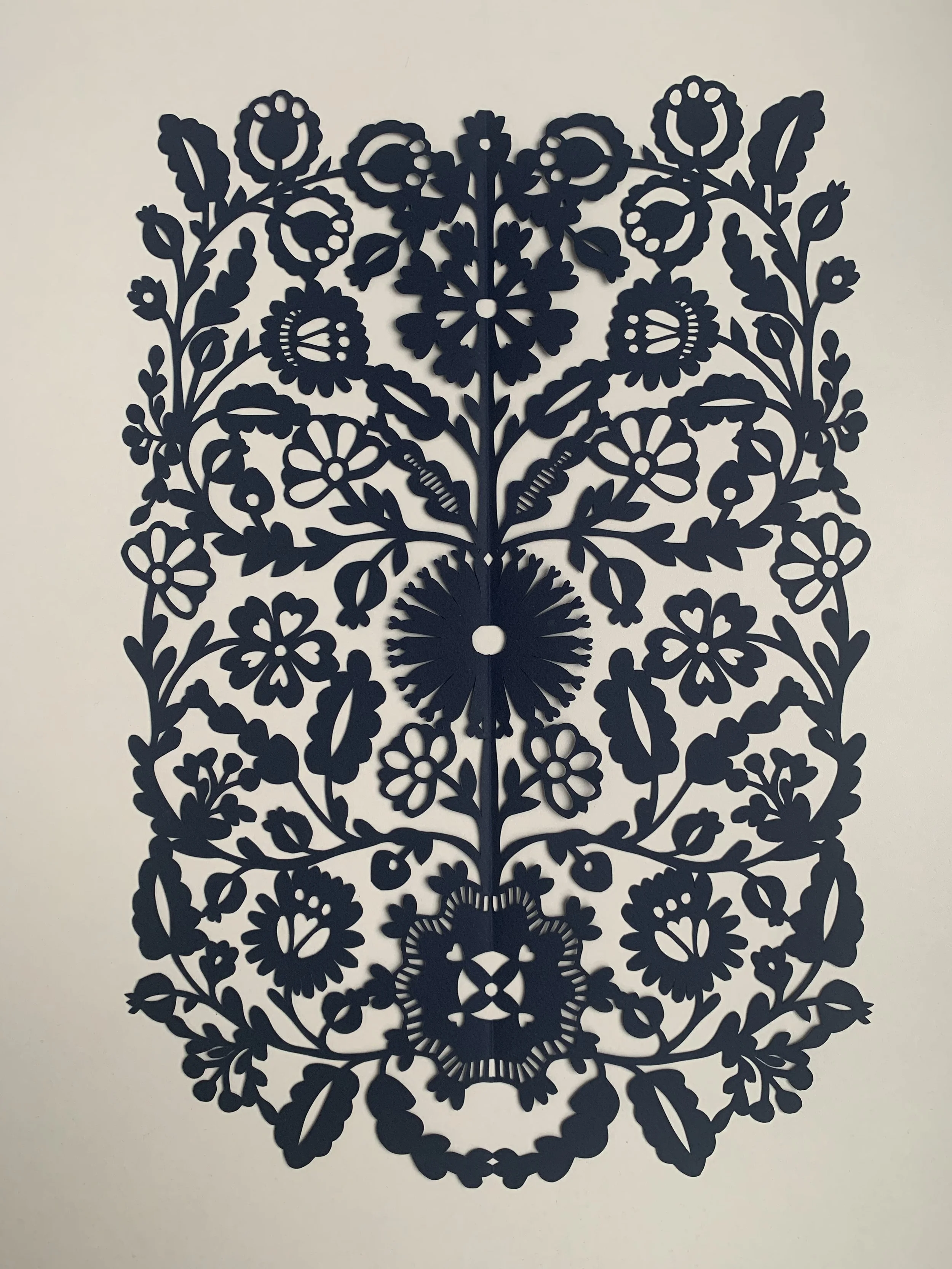

Olena Konohorova is a Kyiv-based artist who creates graphic cut paper (витинанка - vytynankа) designs. She graduated from the H. S. Skovoroda Kharkiv National Pedagogical University (also the alma mater of internationally recognized poet, Serhiy Zhadan) with a degree in the Decorative and Applied Arts. She studied various traditional craft techniques ranging from embroidery, leatherwork, ceramics, pysnaka design, and others - all of which inform her current work.

After a 7 year hiatus to raise her two children, Olena resumed her creative career in 2021. Her work addresses questions of innovation, expression, dedication and discipline.

What is your creative philosophy? What inspires your work?

Originally, vytynankas were used to decorate the interiors of homes - they would be pasted onto crossbeams, walls or windows. In the west of Ukraine they tended to be geometric, while in the east they were more organic and might depict people & animals. Often they would be used for holiday decorations. They were smaller than the works I create and much less detailed, having been quickly shaped with sheers or knives.

I found it interesting that this form of decorative art was always secondary to embroidery, wood carving or beadwork, which was more complex. I like that it’s accessible and ephemeral — that I can take a technique as simple as the one children use to make snowflakes and elevate it

Not many old, authentic vytynanka works remain - paper is not very resistant to fire, water or time. And the truth is I think that’s almost a good thing. Given how saturated we are with images today, I find that it’s easy to inadvertently replicate what we’ve seen elsewhere without even realizing it - I see a lot of that on the internet. I don’t want to get too influenced by others.

Similarly, I believe it’s important to respect tradition, even if copyright laws now longer apply to old works of art. For example, designers appropriate or directly replicate works from the collections of the Ivan Honchar Museum yet don’t contribute any of the earnings back to support the institution.

I strive to create work that is inspired by tradition but does not replicate it. I may use the form of a tree of life but I won’t copy it exactly. I study the principles of a traditional design and try to extract the essential elements, the structure at the core.

At the end of the day, the client is paying for a piece of paper. So this paper needs to carry artistic value, it needs to connect to something deeper, and that value should be innately recognized and felt even by those who aren’t Ukrainian. I don’t think I’m there yet, but that’s what I strive to achieve.

What do you believe is the value in reviving traditional craft techniques in modern times?

We are in the midst of a process of decolonization. We are peeling away layers oppression that started well before the USSR. Language is an easy example - those who start to study their family tree often discover that speaking Russian only runs 2 generations deep, that in fact Ukrainian is their native language.

The same is important to do in the arts - to peel away the layers like an onion and get to the core of our culture so that we can rebuilt from there. Studying the past past allows connects with past generations.

Now, Ukrainians are searching to discover and show their worth to the world. But like the poet Taras Shevchenko said (“Learn my brothers. Think critically, read widely, but do not forget where you came from”), as you are exposed to new ideas, you cannot forget your origins.

You cannot be a person of the world if you don’t know yourself. You need to know your culture and your history so that you don’t get lost in globalization.

I want to create value for my country. I want to make my contribution towards decolonization and development. Through my work, I want show how Ukraine fits in to the context of other Eastern traditions. The paper used for vytynankas came from China and similar traditions developed in Poland, Belarus and other neighboring regions. Through my work - the composition and patterns - I am trying to distinguish the elements that are uniquely Ukrainian.

What inspired you to restart your creative career and how did you select paper as your medium?

After various jobs as an educator, florist and full-time mother, and nearly 7 years without picking up a pencil I felt the need to return to my creative roots. I wanted to feel empowered again. My criteria were that it be 1) grounded in Ukrainian tradition 2) ecological and 3) allow me to work from home. Initially I considered printmaking and linocut, since drawing was always one of my strengths, but quickly ruled it out because of how resource intensive it (it requires a roller press, expensive inks and linoleum, etc.).

Then I saw an advertisement that featured some cut paper elements and I realized - ‘that’s it’’. I started in the spring of 2021 and very quickly cutting these patterns became much more than a creative outlet for me. At the time, the threat of a new wave of Russian aggression was growing and by the end of the year our family had suitcases packed at the door, ready to flee Kyiv at a moment’s notice. We were really living day-by-day. This creative process became a form of therapy and relaxation for me - for those few hours I had full control over that single sheet of paper and could let the stress around me fade into the background.

I live a war zone, I feel a lot of pain. This medium allows me to translate those feelings into something productive.

What was most challenging about restarting?

The hardest part for me was to begin charging for my work. I felt like an imposter, ‘Who am I to charge for my art?’, ‘What will people I respect think of me given I haven’t always been a professional artist?’, ‘Maybe I have lost my creative talents after so much time. I might not have “it” anymore.’

In December 2021 I sold my first two works - I didn’t charge much for them (although they also weren’t cheap) and soon I had long list of order requests.

Our family began regular contributions to the Ukrainian Armed Forces. While it was our family’s donation, it was money my husband earned since I was a full-time mother. I didn’t feel like I was doing enough myself. I wanted to feel useful and like I could make a difference too.

After February’s full-scale invasion started, I lost my hesitation because I could work in service of something bigger than myself. The war taught me to live without fear.

Under the excuse of raising money for the army, I began selling my work without shame, as if the fact that I wasn’t keeping the money myself somehow justified my right to be an artist.

I had a weeks-long waiting list and I was donating 100% of sales towards the war. Day after day I churned out pieces. As the news of the war became scarier, I fell into a deep depression and I felt I couldn’t stop producing Often the money didn’t even pass through my hands, I asked buyers to send money directly to a friend on the frontlines, or to a humanitarian organization. I was totally burned out.

I realized that I had to keep part of the earnings for myself, to slow down a little bit and be more intentional about my work and artistic development. I started to build a portfolio of works so that I one day I can have an exhibition.

What advice would you give other creatives who are (re)starting their careers?

I think you need to be authentic. You need a goal other than fame and success. Your work needs to reflect your personal life, your values, your daily habits. Discover your own creative path and don’t get caught up trying to imitate or mirror what you see on other artists’ pages. If you show what is real, the “branding” will come naturally. I believe that people want to buy art that connects them to an individual.

What does the war mean for Ukrainian culture and design?

Right now we have a unique opportunity to rewrite the stereotypes the world has about Ukraine.

For example, the Soviet Union exploited the kitschy stereotype of sharovarschyna (шароварщина) — a term that stems from a style of pants worn by the Kossaks likely inspired by their Ottoman rivals who wore ‘shalvars’ — is a gaudy representation of Ukrainian culture (e.g., cheap embroidery, plastic flower wreaths).

This sterotype was an easy way for the Ukrainian diaspora and others to access the Ukrainian culture. But I believe now is the moment to we move beyond it. I think that we can develop an image that is more sophisticated - where traditional symbols are referenced but don’t dominate design. For example, President Zelensky and the First Lady often wear Ukrainian symbols, but they tryzub is small, the ethnic motifs subtle.

This is a good start to rethinking the aesthetic component of Ukrainian culture, which represents our people on the world’s stage. But there is still a lot of work to be done. To go back to the onion metaphor, now is the time to research Ukrainian culture more deeply so that we can translate and transmit a nuanced representation of Ukraine.